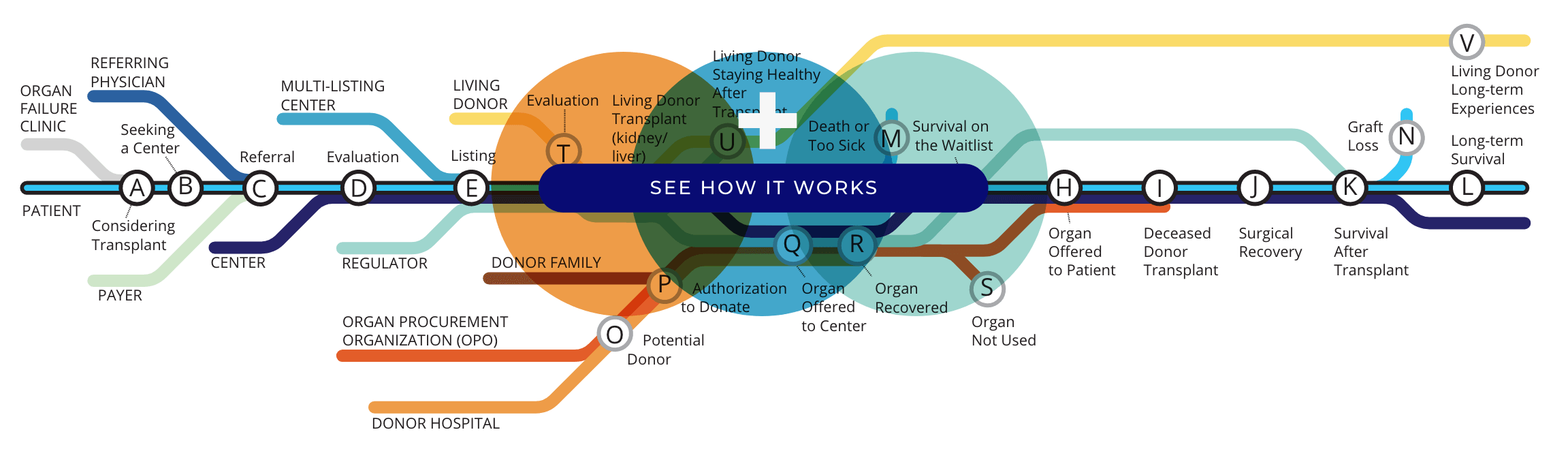

Considering Donation

You can learn more about your options as a potential living donor, including what choices you have about who you donate to and how organ donation can impact you and the people who are in need of life saving organ transplants.

Decide if you would like to donate a kidney to a loved one (directed donation) or someone you don’t know (non-directed donation). For directed donation, discuss your decision with the intended recipient and/or contact their transplant center for information on an evaluation. For non-directed donation, locate and contact transplant centers near you with the SRTR center search page.

Living Donor Evaluation

A potential living donor must complete multiple steps of a thorough medical and psychological evaluation to determine if being a donor is appropriate. Each transplant center has its own evaluation process. Ultimately, an evaluation at a transplant center determines if you are healthy enough to donate.

This may include physical exam, blood compatibility test, psychological assessment, and meeting with an Independent Living Donor Advocate (ILDA). An ILDA ensures that you understand living donor risks and provides the resources you need to decide whether to donate.

Undergoing a psychological evaluation. You may meet with a psychiatrist and/or social worker to review your mental health history and discuss how donating may affect other aspects of your life. Consider joining a support group for living donation, as you will likely need a caregiver for a time after surgery.

Going over financial details. While evaluation and surgery costs are typically paid by the recipient’s insurance, consider if you can afford non-medical expenses like travel, lodging, and time off from work, or whether you would need to seek assistance with the financial burdens of donation.

The evaluation may include discussing whether your decision to donate is entirely your own and not the result of pressure from friends or family.

If the results show you are not compatible with your transplant recipient, you can consider a kidney paired donation exchange program here or here. Kidney paired exchange takes place when two donors are matched with each other’s transplant candidate. This switch allows both to receive a kidney.

After your evaluations, the transplant team will assess your case and determine if you can be a living donor. Depending on the outcome, this may be followed by scheduling your surgery.

You will be scheduled for a living donor kidney transplant surgery. Laparoscopic donor nephrectomy is a common procedure to remove a kidney. This method is less invasive and involves smaller incisions compared to the traditional surgery.

Living Donor Staying Healthy After Donation

After donating, the donor will recover first in the hospital and then at home for a while before returning to normal activities. Recovery time varies for each person. Typically, most people return home after a few days in the hospital. There will be restrictions for a period of time following surgery, such as driving restrictions and limits on the amount of weight you can lift. The donor will be asked by the transplant center to participate in follow-up physical exams for at least two years after donation. The donor will also be encouraged to follow diet and exercise practices to remain healthy.

Living Donor Long-term Experiences

While more long-term studies are needed, available research shows that living donors generally are not negatively affected by donation. The majority return to normal activities and do not experience significant differences in their long-term health. The vast majority of living donors have no regrets about donating and would do it again. However, there are some risks to donating. You can learn more about risks in the section below.

Kidney Transplants

Kidney Transplants

Liver Transplants

Liver Transplants